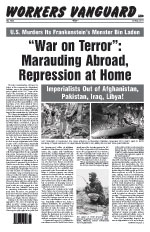

Commemorating the War That Smashed Slavery Finish the Civil War! Black Liberation Through Socialist Revolution! Part Two Below we conclude this article, Part One of which appeared in WV No. 979 (29 April). Racist hostility toward blacks figured prominently in the labor and socialist movements of the late 1800s/early 1900s, with the exception of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). But it was not until the 1920s that American Marxists actively took up the fight for black liberation, as part of the fight for communism. James P. Cannon, a founding American Communist and foremost leader of American Trotskyism for its first 30-plus years, makes very clear how exactly this came about. He writes: “The American communists in the early days, like all other radical organizations of that and earlier times, had nothing to start with on the Negro question but an inadequate theory, a false or indifferent attitude and the adherence of a few individual Negroes of radical or revolutionary bent.... Everything new and progressive on the Negro question came from Moscow, after the revolution of 1917, and as a result of the revolution—not only for the American communists who responded directly, but for all others concerned with the question.” Further: “Even before the First World War and the Russian Revolution, Lenin and the Bolsheviks were distinguished from all other tendencies in the international socialist and labor movement by their concern with the problems of oppressed nations and national minorities, and affirmative support of their struggles for freedom, independence and the right of self-determination. The Bolsheviks gave this support to all ‘people without equal rights’ sincerely and earnestly, but there was nothing ‘philanthropic’ about it. They also recognized the great revolutionary potential in the situation of oppressed peoples and nations, and saw them as important allies of the international working class in the revolutionary struggle against capitalism. “After November 1917 this new doctrine —James P. Cannon, The First Ten Years of American Communism (1962) The Russian Revolution of 1917 was the most important event of the 20th century and is our model for a successful proletarian revolution. As Cannon said, it “took the question of the workers’ revolution out of the realm of abstraction and gave it flesh and blood reality.” It demonstrated that the bourgeois state could not be reformed to serve the interests of the working class but had to be smashed and replaced by a workers state, the dictatorship of the proletariat. It showed the need for a disciplined vanguard party based on a clear revolutionary program. The Bolsheviks’ fight around the American black question is but one example of the hard, programmatic struggle that they waged to forge truly revolutionary Leninist vanguard parties around the world that could serve as tribunes of the oppressed and fight for international proletarian revolution. The Great Migration and Black Proletarianization The defeat of Reconstruction reconsolidated blacks as a race-color caste. But it was the Great Migration of blacks to the North and to the urban centers of the South that established blacks as a strategic component of the proletariat. I recommend this new book by Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration. For those too young to remember, the book gives a vivid picture of the wretched racist conditions of the South, as well as the struggles blacks faced in the North. It follows three different individuals who personify the different directions that this migration took: one who went from Florida to Harlem, one from Mississippi to Chicago, and one from Louisiana to California. It’s a quite literate book; every chapter starts with a poem or quote from a famous black writer. The title, “The Warmth of Other Suns,” comes from a poem by Richard Wright. Let me read the one by Langston Hughes called “One-Way Ticket”: “I pick up my life Before World War I, something like 90 percent of all blacks lived in the South, and they were mostly rural. Wilkerson estimates that six million black people left the South in the decades from 1915 to 1970. That’s a lot of people! In 1910, Chicago had a black population of about 2 percent. California in 1900 had only about 11,000 black people, which was less than 1 percent. When I first read statistics like this, they were hard to wrap my mind around because I had grown up in the 1960s, when the heavy battalions of labor, from longshoremen to auto to steel, were heavily black. This migration and the migration to the urban centers of the South, along with the struggle for industrial unionization in the ’30s, integrated blacks into the labor movement, although still at the lowest rungs and at the dirtiest and hardest jobs. Often blacks played a leading role in these labor struggles. Proletarianization gives you social power—at least, potential social power. Race-Color Caste Now there was an ambiguity which ran through both the Communist Party and later the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in its revolutionary heyday as to whether the black question was a national question, or embryonic national question, and whether the slogan of self-determination was appropriate. Leon Trotsky himself tentatively advanced this position in the 1930s, coming at the question from his understanding of the national question in Europe. Like the early Communist International’s intervention, Trotsky was primarily concerned that the American Trotskyists have a serious orientation to the black question and not capitulate to backward consciousness. In practice, the SWP didn’t act like the black question was a national question and was guided by an integrationist, class-struggle perspective. The party was able to recruit several hundred black workers during World War II by acting as the most militant fighters against racist oppression in the factories, armed forces and American society at large. The SWP’s courageous work, carried out in the face of government repression, was in stark contrast to the Communist Party, which, in line with its support to the Allied imperialist “democracies,” explicitly opposed struggles for black equality during the war. Dick Fraser joined the Trotskyist movement in 1934. He was a founding member of the Socialist Workers Party. He began a study of the black question in the late 1940s in response to the loss of hundreds of black worker recruits with the onset of the Cold War against the Soviet Union. He concluded that the problem was not with the SWP’s practical, day-to-day work fighting discrimination and victimization of blacks but with the party’s inadequate theoretical understanding. As Fraser wrote: “It is the historical task of Trotskyism to tear the Negro question in the United States away from the national question and to establish it as an independent political problem, that it may be judged on its own merits, and its laws of development discovered” (“For the Materialist Conception of the Negro Struggle” [1955], reprinted in Marxist Bulletin No. 5 [Revised]). Fraser began from the premise that black people, whom he described as “the most completely ‘Americanized’ section of the population,” were not an oppressed nation or nationality in any sense. Crucially, black people lacked any material basis for a separate political economy. Whereas the oppressed nations and nationalities of Europe were subjected to forced assimilation, American blacks faced the opposite: forcible segregation. Hence, in the struggle against black oppression, the democratic demand for self-determination—separation into an independent nation-state—just didn’t make sense. As Fraser wrote in his 1963 piece “Dialectics of Black Liberation” (reprinted in Revolutionary Integration: A Marxist Analysis of African American Liberation [Red Letter Press, 2004]): “The Black Question is a unique racial, not national, question, embodied in a movement marked by integration, not self-determination, as its logical and historical motive force and goal. The demand for integration produces a struggle that is necessarily transitional to socialism and creates a revolutionary Black vanguard for the entire working class.” He had earlier noted in “For the Materialist Conception of the Negro Question”: “The goals which history has dictated to [black people] are to achieve complete equality through the elimination of racial segregation, discrimination, and prejudice. That is, the overthrow of the race system. It is from these historically conditioned conclusions that the Negro struggle, whatever its forms, has taken the path for direct assimilation. All that we can add to this is that these goals cannot be accomplished except through the socialist revolution.” In The Warmth of Other Suns, Wilkerson makes a point that confirms Fraser’s point about blacks being the most American of Americans. She poses the Great Migration as a sort of internal immigration. But when she posed this analysis to the over 1,000 black people that she interviewed for this book, “nearly every black migrant I interviewed vehemently resisted the immigrant label.” They insisted that “the South may have acted like a different country and been proud of it, but it was a part of the United States, and anyone born there was born an American.” Further, that “for twelve generations, their ancestors had worked the land and helped build the country.” Indeed, black people’s labor has been central to building this country, but it will take a socialist revolution by the multiracial working class for them to realize the fruits of their labor. Fraser lost the fight in the Socialist Workers Party on the black question. But his work found resonance in the Spartacist League. Despite political differences with him, he was invited to the SL/U.S. National Conference in 1983 and spoke on the question of the organization of labor/black leagues, saying: “I am humbled by the knowledge that things that I wrote 30 years ago, which were so scorned by the old party, have had some important impact, finally.” In the U.S. at the time of the civil rights movement, the SWP was the only organization, at least formally, with an authentically revolutionary program based on Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky. However, by the early 1960s, ground down by the isolation and McCarthyite witchhunting of the 1950s, the SWP had lost its revolutionary bearings. The party’s qualitative departure from its erstwhile revolutionary working-class politics began around 1960, when it slid into the role of uncritical cheerleaders for the petty-bourgeois radical-nationalist leadership of the Cuban Revolution. The SWP thus abandoned the centrality of the working class and the necessity of building Trotskyist parties in every country. The abandonment of the fight for Marxist leadership of the black struggle in the U.S. was the domestic reflection of the SWP’s denial of the centrality of the proletariat in the destruction of capitalism. Its leadership willfully abstained from the civil rights movement while cheerleading from afar for both the liberal reformism of King and the reactionary separatism of the Nation of Islam. This meant that historic struggles that were to shape a whole generation took place without the intervention of a revolutionary party. Contradictions in SNCC Let me say a little more about my experiences in Mississippi in 1965 and how I saw this period. I certainly wasn’t in the Spartacist League; I was unfamiliar with any left group except the Communist Party, which my parents had been members of and which I rejected as very “old school.” My point is that I came back from Mississippi frustrated and confused by my experiences in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). This period is often portrayed in triumphalist fashion: MLK and the good fight against legalized segregation, etc., etc. At first I assumed that my project in Gulfport was particularly disorganized, but in retrospect I could see that SNCC was politically coming apart at the seams. Now SNCC had started as the youth extension of MLK’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. As black liberals, their initial goal was formal, legal equality, or “northernizing the South.” The political strategy was to seek the support of the liberal establishment and try to get the federal government to help black people. That’s really what all this “pacifism” was about—appealing to the Northern Democrats and being respectable. But after some hard experiences in the South with cops, Klan, Democrats, etc., SNCC had moved to the left. When I was in Mississippi, there was a lot of talk about going to the North to confront black oppression there—segregated housing, unemployment, rotten schools, police brutality. The American bourgeoisie might go along with getting rid of legal segregation, but black equality? An end to black oppression? No way—too central to the American capitalist system! And there was no consensus in SNCC on how to deal with capitalism. The only two answers I heard in the SNCC of that time were back to MLK liberalism or an incoherent black nationalist separatism. Without the intervention of communists, most SNCC radicals were not able to make the leap to proletarian socialism. I want to deal with the contradictions that I saw in SNCC. First of all, when I was in Mississippi, the Los Angeles Watts upheaval broke out. Martin Luther King said that “as powerful a police force as possible” should be brought to L.A. to stop it. SNCC activists on my project cursed King’s name because it was clear that he was calling for pacifism for us and guns for the National Guard to put down black people in the ghettos. Then we heard that our project might be attacked by the KKK. So people on my SNCC project proposed talking to the FBI about it. Being a red-diaper baby, I was horrified and opposed to this. I had seen my mother kick an FBI agent in the shins when he tried to barge into my parents’ house. But it was decided, and we all went down there together. The people on my project had assumed the FBI agent would be a Northerner, but he was a real Southerner with a heavy drawl. When he asked for our address, I was shaking my head and trying to get them to stop, but they gave it to him. Soon thereafter we heard through the grapevine that our house was in danger of being bombed! I wasn’t surprised and went around saying “I told you so” for days. Worried about the threats, we moved out of our house for a while. With another young white woman, I went to stay with a very friendly black family. When night fell, they urged me and the other woman to sleep in one of the bedrooms. They kept insisting that there would be “no violence, no violence.” When I looked around the room, I could see that every guy there was holding a rifle or a shotgun. They kept saying that there would be “no violence from the Klan.” I just thought, “Well, this is the kind of ‘non-violence’ I’m for!” The Spartacist League, as you can read in the document “Black and Red,” was certainly for armed self-defense in the South. From my own experience, I think there was a lot more of it actually going on than people realize today. Then we had a community meeting and were going to talk about the work we were doing. I suggested that we talk about this new thing called the Vietnam War. I sure got landed on for that! First, I was told that we were conducting a single-issue campaign around civil rights. When that wasn’t too convincing, I was told that “blacks were very patriotic” and wouldn’t appreciate criticism of American foreign policy. Later when I heard Muhammad Ali saying “No Viet Cong ever called me n----r” and saw that black people hated the war in Vietnam, I was sorry we hadn’t brought it up. I never got to meet the longshoremen I mentioned who threatened to strike if the lunch counters didn’t get integrated. They were just the power in the background, but I was impressed with them. SNCC didn’t know what to do with them, but it seemed to me that there must be some left group out there who knew how to organize the power of labor. In the Spartacist League’s successful anti-Klan united fronts, I saw that power consciously mobilized in the fight for black freedom. Several times people on my project asked me questions about Marxism; I would try to answer but I just didn’t know enough. That’s why it was such a crime and a betrayal that the SWP didn’t intervene. The Spartacist tendency originated in the early 1960s as a left opposition, the Revolutionary Tendency (RT), in the SWP. A central axis of the political fight was for an active intervention into the Southern civil rights movement based on the perspective of revolutionary integrationism—i.e., linking the struggle for black democratic rights to working-class struggle against capitalist exploitation. The SL was small, predominantly white, and the main body of young black activists moved rapidly toward separatism. Northern Ghetto Upheavals With the civil rights movement unable to change the hellish conditions of black life in the North, there was a rising level of frustrated expectations. There were a whole series of ghetto upheavals in the mid to late ’60s that were repressed with extreme police/National Guard violence. As we wrote in “Black and Red”: “Yet despite the vast energies expended and the casualties suffered, these outbreaks have changed nothing. This is a reflection of the urgent need for organizations of real struggle, which can organize and direct these energies toward conscious political objectives. It is the duty of a revolutionary organization to intervene where possible to give these outbursts political direction.” In line with this policy, at the time of the 1967 ghetto rebellion in Newark, New Jersey, we put out a very short agitational leaflet (less than a page, if you can believe) titled “Organize Black Power!” which you can see in Spartacist Bound Volume No. 1. Despite their radical and often white-baiting rhetoric, most of the black nationalists quickly re-entered the fold of mainstream bourgeois politics. They offered themselves to the white ruling class as overseers of the ghetto masses. They became administrators of the various poverty programs and members of the entourage of local black Democratic politicians. The Black Panthers represented the best of a generation of black activists who courageously stood up to the racist ruling class and its kill-crazy cops. They scared the ruling class. In 1968, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover vowed, “The Negro youth and moderate[s] must be made to understand that if they succumb to revolutionary teachings, they will be dead revolutionaries.” This was a blunt statement which was soon put into effect! Under the ruthless COINTELPRO government program, 38 Panthers were assassinated and hundreds were railroaded to jail. It is not an accident that the 17 class-war prisoners who receive Partisan Defense Committee stipends include three who are framed-up former Black Panthers: Mumia Abu-Jamal, America’s foremost political prisoner, brilliant journalist known as the “Voice of the Voiceless,” whose freedom we have fought for over many years; as well as Ed Poindexter and Wopashitwe Mondo Eyen we Langa. Unfortunately, the Panthers, along with most of the New Left, rejected the organized working class as the agent of black freedom and socialist revolution. The Panthers looked to black ghetto youth as the vanguard of black struggle. The underlying ideology of the Panthers was that the most oppressed are the most revolutionary. But, in fact, the lumpenproletariat in the ghetto, removed from the means of production, has no real social power. On another level, despite a lot of very dedicated black women members, the Panthers partook of the black nationalists’ contempt for women. From Stokely Carmichael’s gross statement about the position of women in the movement being “prone,” to Eldridge Cleaver’s rantings about “pussy power,” to Farrakhan, the nationalists seek to keep women “in their place,” often opposing birth control and abortion as genocide. We stand for free abortion on demand and women’s liberation through socialist revolution. As we later wrote in the SL/U.S. Programmatic Statement [November 2000] about black nationalism in all its diverse political expressions: “At bottom black nationalism is an expression of hopelessness stemming from defeat, reflecting despair over prospects for integrated class struggle and labor taking up the fight for black rights. The chief responsibility for this lies on the shoulders of the pro-capitalist labor bureaucracy, which has time and again refused to mobilize the social power of the multiracial working class in struggle against racist discrimination and terror.” And, I would add, today refuses to mobilize class-struggle resistance against the increased immiseration of the entire working class in the midst of the worst depression since the 1930s! We say: Break with the Democrats, for a revolutionary workers party! For a class-struggle leadership of the unions! A Proletarian Revolutionary Perspective The last 30-some years have consisted of all-out union-busting, a determined, and so far successful, effort to drive down the real standard of living for the working class and roll back many of the gains of the civil rights movement. To the extent that schools were ever desegregated, they are now being resegregated and are as “separate and unequal” as ever. The big advance is that the really segregated schools are named for Martin Luther King or Rosa Parks. Under Obama, “school reform” amounts to a massive assault on public education carried out through brass-knuckle attacks on teachers unions. Higher education is becoming a privilege of the rich, with massive fee hikes. I saw more black students at the University of California when I was a student than I do now. Obama may intone that this country has come “90 percent of the way” to ending racism. Perhaps for the very thin layer of black people, like Obama and Oprah Winfrey, who benefited from the civil rights movement, got high governmental posts or made millions of dollars, it looks that way. But for the vast majority of black people, day-to-day life has gotten a lot worse! Then there is government repression: the “war on drugs,” which is a war on black people; the “war on terror,” which is a war on civil liberties; three-strikes laws; mass incarceration of blacks and Latinos; mass deportations of immigrants; FBI harassment and grand jury subpoenas against Midwest leftists; the jailing of radical lawyer Lynne Stewart for ten years; the Muslim Student Union at UC Irvine up on criminal charges for interrupting the speech of the Israeli ambassador; in L.A., outrageous criminal charges against nonviolent acts of civil disobedience in support of immigrant and workers’ rights. The Obama administration has one-upped the Bush administration in its war on civil liberties, and that takes some doing! A liberal columnist writing in the Los Angeles Times (12 February) commented, “From the hysterical reaction of two local prosecutors, you’d think Southern California suddenly had become Paris in 1848 America’s capitalist rulers need their witchhunts as a means to keep those consigned to the bottom of this society “in their place.” Above all, they must suppress the social power of the multiracial working class, for in its hands lies the potential to end the barbarism of capitalist exploitation. Workers have the power to stop the wheels of industry and, through socialist revolution, to reorganize society with a planned socialist economy. The American labor bureaucracy has certainly done a stellar job for the bosses in selling out and holding down class struggle for a very long three decades. So today we meet young people who are interested in Marxism but have never seen a picket line. But capitalism produces class and social struggle by its very nature and by the contradictions inherent in it, often where we least expect it and whether the labor bureaucracy likes it or not. I certainly did not expect that the Near East and North Africa would explode this year. Nor did I expect that there would be mass marches of workers in Wisconsin, of all places, albeit still very much under the sway of the Democrats and bourgeois pressure politics. You can certainly see the anger of the U.S. working class and the contradictions building. Long periods of passivity followed by explosive class struggle is actually sort of a norm for the American working class. What we can and must do now is develop a multiracial and multiethnic cadre that can lead such struggles in the future when the working class moves into action. We need a revolutionary proletarian party based on the understanding that the workers share no common cause with their imperialist masters. You will not get this understanding from labor misleaders or the reformist left, endlessly pushing lesser-evilism and the lie that the capitalists can be made to change their priorities through a little protest and pressure. After all, lesser-evilism just means that when the Democrats get into office, they can do greater evil with lesser resistance! You’re certainly not going to get a Marxist program from groups like the International Socialist Organization, which shows its true colors by having victory parties for Obama’s election when they’re not busy prettifying the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. In conclusion, we fight to build a multiracial workers party that will champion the cause of all the exploited and oppressed in the fight for a socialist America and world. Only then can the wealth produced by labor be deployed for the benefit of society as a whole, laying the basis for eradicating all inequalities based on class, race, sex and national origin. We urge you to join us in the struggle for international proletarian revolution. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||