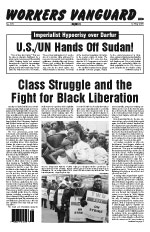

Class Struggle and the Fight for Black Liberation Cruelty and lethal indifference toward working people, black people and immigrants are the hallmarks of the U.S. government and the capitalist class it represents. Even as profits and the stock market rise, FEMA continues to slash disaster relief for the thousands upon thousands of poor, largely black New Orleanians dispersed first by flood waters and then by government policy. It’s the biggest population displacement since the 1930s Depression era and the Dust Bowl. The U.S. government—under both Democratic and Republican administrations—knew for decades about the dangers facing New Orleans but did nothing to reinforce the city’s inadequately built and crumbling levees. When Hurricane Katrina hit, masses were simply left to drown. The aftermath of the hurricane was a racist atrocity that continues, over eight months later, in the forced diaspora of much of the black population that gave this storied city its lifeblood. The infamous FEMA has now ruled that one-third of some 55,000 families still unable to either return home or afford other housing are “ineligible” for financial aid for housing and utilities that was supposed to last for a year. The other two-thirds of the displaced families have to sign new leases while their benefits are cut and they have to pay gas and electric bills. For most of them, there is nothing left in New Orleans to return to. In Memphis, which has 1,500 such families on vouchers, a spokesman for a community services agency said that FEMA even asked these impoverished people to give their kitchen pots and pans back! This comes as Bush’s cronies continue to reap windfall profits from the Katrina disaster, including, according to a Wall Street Journal (5 May) article based on a Congressional report, big contractors who “overbilled the government in a $63 billion operation that only will get more expensive.” The death and devastation along the Gulf Coast was a product of the capitalist system, in which a tiny class of obscenely rich owners extracts its profits from the exploitation of the working class. The human toll of this brutal system can be seen in the rulers’ attempts to dump retirement and health care benefits for workers after years of grueling toil on assembly lines or in other dangerous jobs. It can also be seen in the all-sided attacks on immigrant rights and the threats to further militarize the border by Republicans and Democrats alike. Dangerous working conditions are the norm in the drive for profits, as shown by the disaster last January at the International Coal Group’s Sago Mine in West Virginia, which left 12 miners dead. Now Randal McCloy Jr., the lone survivor at Sago, only recently able to speak again, has told the victims’ families that the company’s emergency breathing equipment failed at least four of the men, so, as they slowly suffocated deep underground, they had to share their last breaths of oxygen. “As my trapped co-workers lost consciousness one by one, the room grew still and I continued to sit and wait, unable to do much else,” he wrote in late April. At hearings concluded on May 4 in Buckhannon, West Virginia, relatives of the dead miners assailed the company and government. “You guys are investigating International Coal Group,” said the son of one of the miners. “Who’s investigating M.S.H.A. [the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration] and the state?” The company has tried to claim that a bolt of lightning four miles away somehow made its way across the Buckhannon River and dove deep underground to cause the explosion. As a United Mine Workers spokesman put it, “You know, if it was lightning then that’s an act of God. And you can’t sue God.” In reality, with coal production expanding, cascading layers of cost-cutting on safety, with the government’s collusion, led to this disaster. Sago Mine was a deathtrap—no exhaust airshaft to remove gas, no escape route—and it was non-union. Any real measure of protection gained by mine workers—or elsewhere in industry—was won through hard struggle by the unions. As we wrote in “West Virginia Mine Disaster: Capitalist Murder” (WV No. 862, 20 January): “With the overwhelming majority of U.S. workers unorganized, what is desperately needed is a class-struggle fight to organize the unorganized—from Appalachia and the West to the notoriously anti-union South.” Such a struggle requires fighting against the policies of the pro-capitalist union misleadership that by and large has renounced the class-struggle methods that built the unions and in some instances (e.g., Delphi auto parts and General Motors) has actually helped to liquidate workers’ hard-won gains. The labor bureaucracy has hamstrung labor’s power through its reliance on capitalist politicians and government agencies. To defeat the capitalists’ unrelenting war against workers and minorities requires the forging of a revolutionary workers party that will lead all the exploited and oppressed in the fight for socialist revolution. Such a party can only be built through combatting the structural oppression of the black population, rooted in the very foundations of this capitalist society. We print below a presentation by Spartacist League Central Committee member Don Alexander, edited and abridged for publication, at a Black History Month educational in Chicago on February 25 that also featured a presentation on the fight for freedom for Mumia Abu-Jamal. Particularly in light of the massive nationwide mobilizations for immigrant rights on May 1 and before, comrade Alexander’s speech serves to illuminate that there will be no effective resistance to the immiseration of American working people without the unity in struggle between the trade unions and the black and Hispanic poor. * * * The fight for black freedom is a strategic task for proletarian revolution in the U.S. A class-conscious labor movement under revolutionary leadership must and will take up the fight for black liberation as an inseparable part of the struggle for the emancipation of workers from capitalist exploitation. We say: Finish the Civil War—For black liberation through socialist revolution! It took a bloody civil war—a social revolution—for black people to be considered persons. There have been centuries of racial oppression in the U.S., and anti-black racism has been central to the maintenance of this capitalist system. There can be no socialist revolution in this country unless the proletariat—the working class—takes up the fight for black liberation, and there can be no liberation of black people short of the overthrow of this racist capitalist system. We fight for the class-struggle program of revolutionary integrationism. This is a fighting program counterposed to liberal integrationism, the false view that blacks can achieve social equality within the confines of racist American capitalism. Today you see the democratic mask falling from the face of the bloody, hypocritical, lying U.S. ruling class. They torture with impunity. Under their system, black people are expendable. During Hurricane Katrina, poor, mainly black people were allowed to die in New Orleans by this racist capitalist ruling class. Thousands continue to face indescribable immiseration, scattered throughout this country and rendered jobless, homeless and rootless. Hurricane Katrina laid bare the naked reality of racial and class divisions at the heart of this sick society. Black people were met with police intimidation and repression at every turn for simply trying to survive. Any kind of assistance was thwarted. The capitalist vultures today are supposedly “rebuilding” New Orleans—by discarding the public education system, bringing in more charter schools, getting rid of the unions and keeping as many black people from returning as possible. This is accompanied by a very conscious attempt to foment racial divisions between black people and Hispanics for the most meager, low-paying jobs. As communists, we denounced the racist atrocity in New Orleans. We called on the multiracial labor movement to fight to win union jobs at union wages, to organize the unorganized, to fight against the oppression of black people, and to enlist the victims of Hurricane Katrina in the rebuilding of New Orleans. Instead of blacks against immigrants and vice-versa, we fight for jobs for all, for full citizenship rights for all immigrant workers, and against the bourgeoisie’s divide-and-conquer schemes. Reconstruction and the Betrayal of Black Freedom The U.S. in its colonial origins was rent by two distinct rival economic systems: black chattel slavery in the South and the so-called “free” labor system in the North. The economic interests of the Southern slaveholder, which required expansion, came into collision with those of Northern capitalists, resulting in bloody civil war. The Civil War was America’s second bourgeois revolution, which culminated in the destruction of the Southern slavocracy. The post-Civil War Reconstruction period, which was brief, was the most democratic, egalitarian period in U.S. history. It brought not only black enfranchisement but other significant democratic reforms. But the Northern capitalists betrayed the promise of black equality, allowing it to be smashed by Ku Klux Klan terror. The Northern capitalists had fought during the war in defense of their property rights, and now the Northern banks sought to exploit the new economic opportunities in the South. The last of the federal troops were pulled out of the South by the Compromise of 1877 and political power was returned to elements of the former slaveholding class. Intensive exploitation of black agricultural labor, rather than industrial development and capital investment in agriculture, remained the basis of the Southern economy. The rigid system of Jim Crow segregation—that is, race-caste oppression—was the bitter fruit of the defeat of Reconstruction. This corresponded to the rise of U.S. imperialism at the end of the 19th century, manifested in particular by the 1898 Spanish-American War, which inaugurated the brutal exploitation of U.S. imperialism’s dark-skinned colonial slaves overseas. The defeat of Reconstruction was not simply the result of internal economic and political factors. There were other powerful factors, including internationally. Just take New York. Manhattan was a city of militant opposition to Reconstruction. Ruled by the pro-Confederate slavocracy Democrats under William Marcy “Boss” Tweed and his corrupt Tammany Hall administration, New York City from late 1865 on was, as historian David Quigley put it, “the Northern capital of anti-Reconstruction activism” (Second Founding, 2004). Class struggle in France haunted the Northern capitalists. In particular, the Paris Commune of 1871 concentrated their minds. New Yorkers of all classes watched with great interest the revolutionary development of the Paris Commune, in which the workers briefly, for the first time in history, set up their own government. Some of the Communards who escaped the mass butchery of the French counterrevolutionaries escaped to New York City, which made the propertied classes, the bourgeoisie, very nervous. Conservative New Yorkers viewed any and all evidence of local working-class unrest through a French lens, finding a wealth of evidence for the rising threat of communism on this side of the Atlantic. E.L. Godkin, the editor of the liberal Nation magazine, the same magazine around today, moved from supporting the anti-slavery Republicans and embraced the Democrats. Godkin complained that patriotism was giving way to “a strong class feeling.” The capitalists then and now were conscious of their class interests. Working-Class Rights and Black Rights Must Go Forward Together Until the substantial entry of blacks into industry during World War I, anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic bigotry were the chief weapons of the rulers in dividing and holding back the working class. Virulent racism against Chinese and Japanese on the West Coast, and the playing off of many ethnic groups against each other in the East—anti-Irish, anti-Italian, anti-Jewish—was the norm. Poisonous ethnic and racial divisions can be broken down in the course of class struggle. A recent example of this was the New York transit strike, when the bosses sought to split the workers through racist demagoguery. You all recall that talk about the workers, in a heavily black union, being “thugs.” That’s what the bosses were saying against the union. Such ethnic divisions have historically impeded the construction of a workers party standing in opposition to both parties of the ruling class. Anti-black racism is the key weapon employed by the capitalist exploiters to divide and hold down the entire working class, and to prevent the working class from becoming what Marx called “a class for itself”—a class fighting to abolish capitalist wage slavery. Now, many reformists and liberals push so-called “people of color” politics, which indiscriminately lumps together the diverse history and struggles of non-whites in this country. This is what we call a sectoralist perspective, which counsels each sector of the oppressed to mobilize on behalf of its own constituency, appealing to the Democratic Party for a few crumbs. What we fight for is a Leninist vanguard party that is a tribune of the people, that champions the interests of all the oppressed and the exploited. “People of color” liberalism also negates the centrality of the fight against black oppression, which is a motor force for the fight for proletarian revolution in the U.S. The majority of black people, as a race-color caste segregated at the bottom of society, face brutal daily racist subjugation and humiliation, by whatever index of social life one might choose—joblessness, imprisonment, lack of decent integrated housing—in this so-called “democracy,” a democracy for the rich. On the other hand, and crucially, black workers are a strategic part of the proletariat in urban transport, longshore, auto, steel (what remains of some of those industries), and they are the most unionized section of the working class. They form an organic link to the downtrodden ghetto masses who are valuable potential allies in the class struggle against the capitalist rulers. Being strategically located in the economy and facing special oppression, black workers under revolutionary leadership will play a vanguard role in the struggles of the entire U.S. working class. Class-conscious black workers, armed with a revolutionary program, can play a central role in building a multiracial workers party. The capitalist rulers note and fear this, along with their labor lackeys. Marxists and the U.S. Civil War The Spartacist League, as a fighting revolutionary Marxist organization, stands in the heroic tradition of the mid 19th-century revolutionary abolitionists John Brown, Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass; of the founders of scientific socialism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, and the Bolsheviks under V.I. Lenin and Leon Trotsky, who led the workers revolution of October 1917 in Russia; and of the German Communists Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht and others. Karl Marx stated shortly after the Civil War that “Labor cannot emancipate itself in white skin where in the black it is branded.” In his pamphlet Wage-Labor and Capital, a series of lectures to the German Workingmen’s Club in Brussels in 1847, Marx sought to throw a historical light on the nature of the black question. He wrote: “What is a Negro slave? A man of the black race. The one explanation is worthy of the other. A Negro is a Negro. Only under certain conditions does he become a slave. A cotton-spinning machine is a machine for spinning cotton. Only under certain conditions does it become capital.” He was addressing the material basis of that oppression, which is exactly what we as Marxists seek to do. Now, in order to win we have to have a program that is revolutionary, proletarian and internationalist. Revolutionary German workers came to the United States following the defeat of the 1848 revolutionary wave in Europe and helped to overthrow slavery. They led regiments in the Union Army. They were animated by revolutionary ideals. Marx and Engels played a key role in winning English weavers and spinners of the cotton industry to the cause of victory for the forces of the Northern army and in impeding the ruling classes in England and France from supporting the Confederacy. These workers in England endured great privations and suffering. But they saw that they had an interest in fighting to get rid of black chattel slavery. Armed black freedmen, ex-slaves, 200,000-strong in the Union Army and Navy, were powerful instruments that helped smash slavery. They made a huge difference in the war both strategically and symbolically. Frederick Douglass called black enlistment in the ranks of the Union Army “the greatest event of our nation’s history, if not the greatest event of the century.” Ulysses S. Grant said, “I have given the subject of arming the Negro my hearty support. This, with the emancipation of the Negro, is the heaviest blow yet given the Confederacy…. By arming the Negro we have added a powerful ally.” It was no accident that many captured black Union soldiers were massacred by the Confederate army. The black people in Louisiana have a proud history of fighting for freedom. The book Generations of Captivity [2003] by Ira Berlin describes an incident during the Civil War when slavery was collapsing. When “the manager of the Magnolia plantation in Southern Louisiana dismissed the slaves’ claim for wages, the slaves erected a gallows within the shadow of the Big House.” When the masters learned the slaves intended to hang them so that “‘they will be free,’ the masters paid up and fled.” The slaves had the Union Army behind them. And today we fight to mobilize the social power of the army of labor behind the fight for black liberation in this country. Marx and Engels, in their writings on the American Civil War, were critical of the timidity of Lincoln’s Republican Party and its policies of conciliation toward the slaveholders, manifested for example in the role of General George McClellan, who led the Union Army for a period. In 1937, Leon Trotsky, who fought against the politics of class collaboration embodied in the “Popular Front,” raised the example of the American Civil War to drive home the bankruptcy of conciliating the class enemy. He wrote: “In civil war, incomparably more than in ordinary war, politics dominates strategy. Robert Lee, as an army chieftain, was surely more talented than Grant, but the program of the liquidation of slavery assured victory to Grant. In our three years of civil war [in Russia], the superiority of military art and military technique was often enough on the side of the enemy, but at the very end it was the Bolshevik program that conquered. The worker knew very well what he was fighting for.” —The Spanish Revolution Now, whether Lee was more talented or not, we know that it is important to know what you are fighting for. To paraphrase an old African proverb: If you don’t know what you are fighting for, any road can take you there. The Communist International and the Black Question The early Communist International—the Comintern—under Lenin and Trotsky was assisted by American Communists such as John Reed and also the radical West Indian poet Claude McKay, both of whom provided useful information on the situation of blacks in the U.S. The revolutionary Trotskyist James P. Cannon eloquently indicated in his very important essay “The Russian Revolution and the American Negro Movement” [International Socialist Review, Summer 1959; reprinted in The First Ten Years of American Communism, 1962] that the assistance rendered by the Bolsheviks to the early American Communist Party in overcoming its colorblindness on the race question, which was a big defect of the early socialist movement in the United States. The Bolsheviks made the argument that black people in the United States were not just exploited as workers but oppressed as black people. There was racial oppression—special oppression—that had to be combatted as part of mobilizing the working class to fight for power in this country. That was an important contribution, and it was made as a result of the fact that they were thoroughgoing internationalists fighting for world proletarian revolution. However, in 1928, at the Sixth World Congress of the Stalinized Communist International, there was invented a so-called “black nation” supposedly situated in the collection of majority black counties in the Deep South that they called the “Black Belt.” This was Stalin’s contribution to the black question. Initially this reactionary line was opposed, especially by some of the leading black Communist Party [CP] cadre. Even the ultra-Stalinist Harry Haywood, the ex-CPer who was a fervent champion of this line, admitted in his autobiography Black Bolshevik [1978] that it didn’t go down well. It smelled like segregation. In spite of this erroneous line, however, in the early 1930s the Communist Party waged an aggressive fight for black rights and equality—against evictions and against rampant police brutality and murder. They organized sharecroppers in the South. They did some very courageous work. This changed with the Stalinists’ embracing of the program of the Popular Front. This program meant subordinating the struggles of blacks and workers to the government of Franklin D. Roosevelt, to the Democratic Party and the capitalist system. It meant opposing the struggle of black people during World War II, and it meant opposing workers’ strikes. It meant supporting the wartime internment of the Japanese. It meant supporting the aims of U.S. imperialism during the second interimperialist world war, which was a war for the redivision of the world. Whatever lack of knowledge Trotsky had on the historical development of black oppression in the U.S. (and he readily acknowledged this), his impulse was to urge revolutionaries to pay special attention to this question. In his 1939 discussions with the Trotskyists in the U.S. at that time, the Socialist Workers Party [SWP], he was particularly concerned that they have a serious orientation to the black question, or they would run the risk of adapting to backward consciousness within the working class. Trotsky stated: “We must say to the conscious elements of the Negroes that they are convoked by the historic development to become a vanguard of the working class.... If it happens that we in the SWP are not able to find the road to this stratum, then we are not worthy at all.” The SWP, Black Nationalism and the Civil Rights Movement The SWP waged an aggressive fight for black rights and equality during World War II. That is our tradition. The Socialist Workers Party was heavily involved in campaigns and struggles against discrimination and segregation. They sought to link the fight for the defense of black rights to the working-class struggle against capitalism. Their interventions were animated by a militant integrationist perspective. They recruited hundreds of black workers and made a significant breakthrough in Detroit. However, as Richard Fraser, the veteran Trotskyist, later noted in his writings, the SWP was politically disoriented. They pushed black workers toward joining the petty-bourgeois, liberal-integrationist and legalistic NAACP, which had grown quite a bit in the post-World War II period. In 1953, Richard Fraser gave two lectures to the SWP on the black question (reprinted in In Memoriam—Richard S. Fraser, Prometheus Research Series No. 3). His main opponent on the black question at that time was George Breitman, who was the principal SWP spokesman for years on this question. Breitman argued that self-determination applied to black people in the U.S.—that is, it was a national question, the right of an oppressed nation to set up its own separate state. Breitman’s program of self-determination was a capitulation to black nationalism. But for the time being, there was no difference between the two lines in terms of the public policy and practical work of the Socialist Workers Party. Fraser argued that self-determination was being misapplied to American blacks. Unlike the oppression experienced by non-Russian nationalities in tsarist Russia, who were subject to forcible assimilation, the exact opposite dynamic was operating in the U.S. That is, the historic tendency of black struggle was for equality, for integration, against segregation and for elementary democratic rights. In Fraser’s powerful 1955 polemic “For the Materialist Conception of the Negro Question” [reprinted in Marxist Bulletin No. 5 (revised), “What Strategy for Black Liberation? Trotskyism vs. Black Nationalism”], he cogently argued that black people were not a nation for whom the demand for self-determination applied. There is no economic basis for a separate political economy for black people, a separate mode of production and commodity exchange. When I first saw his article in 1971, it bothered me a lot: “For the Materialist Conception of the Negro Question.” We were kind of literal-minded, and it was out of step with the times. I said, “This is quaint—we are black people.” But the comrade who sold it to me argued against the prevalent misconception that the oppression of blacks was a “national question.” So I hung on to the pamphlet. I was under the sway of so-called “revolutionary nationalism,” which was a contradiction in terms, because nationalism is a form of capitalist ideology that presumes a fundamental unity of interests between the workers and the bourgeoisie. By 1955, the differences within the SWP over the black question were emerging. This was reflected in the debate over the call for federal troops—the armed forces of the federal government—to defend the black masses in the struggle for civil rights in the South. The demand for federal intervention in Mississippi was raised by the SWP. And Fraser denounced it. By 1957, the SWP supported Republican president Eisenhower’s introduction of federal troops into Little Rock, Arkansas, which crushed developing black self-defense efforts. In 1957, an SWP convention passed a resolution, despite some opposition, promoting the myth that the federal troops were on the side of the oppressed, instead of being an instrument of class oppression, reflecting a revision of the Marxist understanding of the bourgeois state. Fraser had his own tendency within the SWP in 1957, and by 1963 he was in opposition to the majority leadership under Farrell Dobbs. It was known as the Kirk-Kaye tendency, and at the 1963 SWP convention they submitted a resolution upholding the program of revolutionary integrationism. The Revolutionary Tendency, a left-wing opposition within the SWP that was the forerunner of the Spartacist League, supported the resolution while advocating an aggressive communist intervention into the civil rights struggles to take advantage of a time-limited opportunity. The SWP rejected this perspective. [For more on Richard Fraser and his legacy, see the two-part article “Revolutionary Integrationism: The Road to Black Freedom,” WV Nos. 864 and 865, 17 February and 3 March]. We have paid an incalculable price for the abstention of the rapidly rightward-moving Socialist Workers Party during the civil rights movement. An entire generation of radicalized black youth, which had gained experience and authority in the Southern civil rights movement, was lost to the revolutionary movement. By 1963 the SWP had explicitly renounced the fight for communist leadership of the black struggle, relegating itself to the role of a “socialist” vanguard of the white working class. The Revolutionary Tendency fought this liquidationist perspective. We fought for the necessity of a Leninist vanguard party. In an August 1963 document, “The Negro Struggle and the Crisis of Leadership,” the Revolutionary Tendency wrote: “The rising upsurge and militancy of the black revolt and the contradictory and confused, groping nature of what is now the left wing in the movement provide the revolutionary vanguard with fertile soil and many opportunities to plant the seeds of revolutionary socialism…. We must consider non-intervention in the crisis of leadership a crime of the worst sort.” Winning over and forging black communist cadre with authority, rooting them in the black working class in the South, could have changed the course of U.S. and world history. In historical terms, the civil rights movement confronted the unfinished business and tasks of the Civil War. We raised the need for a Southern-wide Freedom Labor Party as an expression of working-class political independence and the need to mobilize the labor movement to fight for black emancipation. We linked this to other demands, including organizing the unorganized, for a sliding scale of wages and hours to combat unemployment and inflation, for the right of armed self-defense against racist terror, and for a workers’ united front against government intervention in the labor movement and against suppression of black struggles. We recognized the need for special organizational forms to win specially oppressed strata to the revolutionary party. So we projected the need for a transitional organization to win over black militants, an organization that would be politically subordinated to, but organizationally independent of, the party and linked to the party through its most conscious cadres. That’s why the Labor Black Leagues exist in a few cities, to provide a vehicle for those who want to fight for a class-struggle program for black freedom and for workers revolution. Ghetto Rebellions and “Black Power” The liberal-led civil rights movement, embodied in Martin Luther King’s “turn the other cheek” pacifism, aimed its strategy at pressuring the racist federal government and the Dixiecrat Democratic Party to fight for black rights. The Democratic Party was an alliance between Northern liberals and the virulently racist Southern Dixiecrats, and this repelled the radicalized black youth. The New Deal-derived labor-black Democratic Party coalition forged under the Roosevelt administration was shattered by the civil rights struggles in the South. The civil rights movement could not achieve black freedom because its leadership and program were based upon support to the Democrats and the racist capitalist system. When it went North, it had no answers to the burning economic oppression of the black masses, who were permanently consigned to the ghettos, who were the last hired and the first fired, who faced rampant police murder and lower life expectancy. Today’s beneficiaries of that struggle, petty-bourgeois “leaders” such as Al Sharpton, Jesse Jackson, Congresswoman Barbara Lee, and ex-Black Panthers such as Congressman Bobby Rush, keep blacks tied to the Democrats and confine their struggles within the framework of capitalism. Anti-Semitic nationalist demagogue Louis Farrakhan offers, as an “alternative” to the bankrupt black “leadership,” reactionary, dead-end black capitalist schemes designed to exploit the ghetto poor while making a virtue out of the segregation imposed upon the black masses. The collapse of the civil rights movement led to ghetto upheavals that were violently suppressed by the armed forces of the racist rulers—the cops and National Guard. My awakening corresponded to that. The suppression of the black rebellion in Watts in South-Central Los Angeles in 1965 was supported by Martin Luther King. Watts was the symbol of the angry black ghetto. From 1964 to 1968 there was a series of black ghetto revolts that were leaderless, that expended a lot of energy with very few results. There was an acutely felt sense that the civil rights movement did not and could not address the burning needs of the masses. It was the case that its legalistic program brought the legal and social structure of the South in alignment with the rest of the country. But it could not get rid of black oppression short of mobilizing to get rid of capitalism. The failure of the labor movement to mobilize its social power in support of black democratic rights fed the development of a separatist mood expressing despair at the possibility of waging an integrated struggle for black freedom. When ex-civil rights activist John L. Lewis, who is now a Democratic Party Congressman from Georgia, tried to put in his speech at the 1963 March on Washington language expressing criticism of the Democratic Party, the labor faker and United Auto Workers head Walter Reuther and the various other Democratic Party bigwigs muzzled him. By 1966, civil rights organizations such as the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee [SNCC] came out for “black power,” which shocked the liberal establishment. After some internal struggle and clarification, the Spartacist League fought to pose the demand for “black power” in class terms and warned that otherwise it would be a bridge to reconciliation with the Democratic Party and co-optation by what was commonly referred to as “the racist power structure.” And man, a lot of militants were being co-opted. We referred to them as “poverty pimps,” with these government poverty programs which were basically to cool down the ghetto and keep people in line. During that period the Spartacist League lacked the numbers and the political authority to influence the agonizing debate and soul-searching that was going on within the ranks of organizations such as SNCC that had broken from mainstream liberalism but had not yet embraced utopian black separatism. The program of black separatism was incapable of generating a program of struggle because it was based upon acquiescence to the racist capitalist status quo and made a virtue of segregation. It propagated the myth that black people, no matter what class they belong to, have the same interests. Then and today there was a third way, an alternative to the program of liberal integrationism and black separatism. And that’s the program of revolutionary integrationism—a class-struggle fight for black freedom. The Black Panthers and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers In 1966, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was formed in Oakland, California. The Panthers were the hegemonic radical black nationalist organization among militant black youth. They were very contradictory. They fought initially to organize independently of the Democrats and Republicans. So-called “revolutionary internationalists,” they were a product of the New Left. They viewed the working class as “bought off” and hopelessly backward. In particular, they promulgated the myth of the “lumpen proletariat vanguard”—the brothers on the block, the streetwise black youth—as the revolutionary vanguard of social change in this country. The Panthers were all over the map politically, eclectic radicals. Their Marxism was kind of a smorgasbord. They heavily borrowed from Mao, guerrilla groups, Stalin, whatever. They were heavily influenced initially by the writings of Frantz Fanon, a supporter of the Algerian National Liberation Front. His The Wretched of the Earth [1961] had a powerful impact especially on black radicals. Fanon was the quintessential “Third World” nationalist, who equated the working class in the capitalist countries with their own rulers. The Panthers argued that black people in the U.S. were a “black colony”—though not of the classic sort, with an imperialist power exploiting non-white masses. This was emotionally seductive and deeply impressionistic. Seductive, because from the standpoint of a ghetto-based political struggle, they could point to an “occupying army,” namely the murderous racist police. The “black colony” line was used mainly to justify their nationalist perspective of black people going it alone, independent of the rest of American society—especially the working class. This utopian program of “community control” of impoverished, segregated ghettos was a proven dead end, and it distracted from the fight for workers revolution to liberate all of the oppressed and exploited. In 1971 there was a split in the Panthers between the pro-Democratic Party Huey Newton wing and the self-proclaimed “urban guerrillaist” (mainly on paper) Eldridge Cleaver wing. This was accompanied by internecine bloodletting fanned by the flames of FBI COINTELPRO provocation. Despite the Black Panthers’ penchant for physical attacks against other leftist critics, including Progressive Labor and ourselves, we defended them against bloody state repression. We raised our criticisms of their program and fought to win the best elements to a revolutionary proletarian perspective. You can see how we intervened in our article “Rise and Fall of the Black Panthers: End of the Black Power Era,” reprinted in Marxist Bulletin No. 5. The League for Revolutionary Black Workers was another radical black nationalist organization on the scene. In 1970-71, I was studying abroad in Beirut. I was a member of the YSA (the SWP’s youth group, the Young Socialist Alliance) and SWP and wrote some reports on the plight of the Palestinians for the SWP. The Black Panther Party leadership, mainly the New York Panthers, was in exile in Algiers and there were other black militants traveling in the region. At one conference in Kuwait I met John Watson, a leader of the Detroit-based League of Revolutionary Black Workers. He was there to show their film on the struggles of black auto workers in Detroit, Finally Got the News. Watson was interesting, he was smart, he was articulate, he was serious—he was a little older than myself. We met again. We had a long discussion on our respective political histories, and on the struggle for Palestinian national liberation, which black radicals were especially interested in then. What was running through my head was, how could I interest him in the SWP? At the time I thought it was revolutionary and Trotskyist. Well, he knew more about the SWP than I did. He told me that he once had a lot of respect for the SWP and that he and black militant friends of his had regularly attended their Militant forums, but eventually they decided that they needed to form their own “black revolutionary party.” The SWP was chasing the pacifist preachers and the black nationalists simultaneously because they had already given up on fighting for a revolutionary working-class program. The SWP offered them a separate black party, so they concluded: Why hang around the SWP? Why not form their own party? Which is exactly what they did. And program is key. When we say program is primary, it’s not an abstraction. It determines where you’re going, what you’re fighting for. I’ve thought a lot about what it would have meant to have won such militants to the Spartacist League and to our Trotskyist program. The League was a radical nationalist workerist organization, but they rejected common struggle with white workers, and they lumped white workers together with the white racist rulers and the racist trade-union bureaucracy. This was a fatal error that sealed their doom. When they split in 1971, a wing of them coalesced around the “radical” lawyer Ken Cockrel, who went into the Democratic Party. The other wing around General Baker and Luke Tripp went into a hard Stalinist group called the Communist Labor Party, which had some influence among militant black auto workers. Now if you claim a “working-class orientation” but you argue that the white population is a single reactionary mass and refuse to give white workers leaflets—which they did—then the bourgeoisie wins and the proletariat loses. There is no substitute for building a Leninist vanguard party that fights against all social oppression, modeled on the Bolshevik Party under Lenin and Trotsky that made the only successful workers revolution in history. There is no substitute for studying genuine Marxism, that is, Trotskyism, the Marxism of our time. It is the indispensable weapon in the struggle for a communist future for humanity.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||